The Horizons We Invent

SANTIAGO GIL

I came back so that life wouldn’t slip away from me unnoticed. I wanted to see sunrise and sunset every day, to sit and watch the ocean and keep looking for chimeras beyond the horizon. I lived in Düsseldorf for the last thirty years. Now I still work there, but looking out over the Las Canteras beach. I left Gran Canaria after finishing my degree in computer science. I used to come back every summer and also at Christmas. I never stopped coming at Christmas.

Now I live here, and I travel to Germany, the United States or Japan to continue developing all the Artificial Intelligence programmes I am involved in.

I was one of the first to see the future in ChatGPT and I am still amongst those who know the most and can contribute the most to its advancement. That’s why I can live in Gran Canaria. I have earned a lot of money, and I decide the conditions of my contract. This text could also be written by the AI; but the AI does not have the memory of my subconscious, nor can it feel what I need to feel when I my memories in writing or when I want to bring back to life those who are no longer there. I learned that as a child in front of this same ocean that never stops moving so that we don’t forget the travelling and changing condition of our own existence. Nor did it know my grandmother, nor does it recognise the aroma of marzipan that I am able to smell just like when I used to go up to Tejeda every year with my grandfather, just before Christmas Eve.

‘….I came back so that life

wouldn't slip away from me unnoticed”

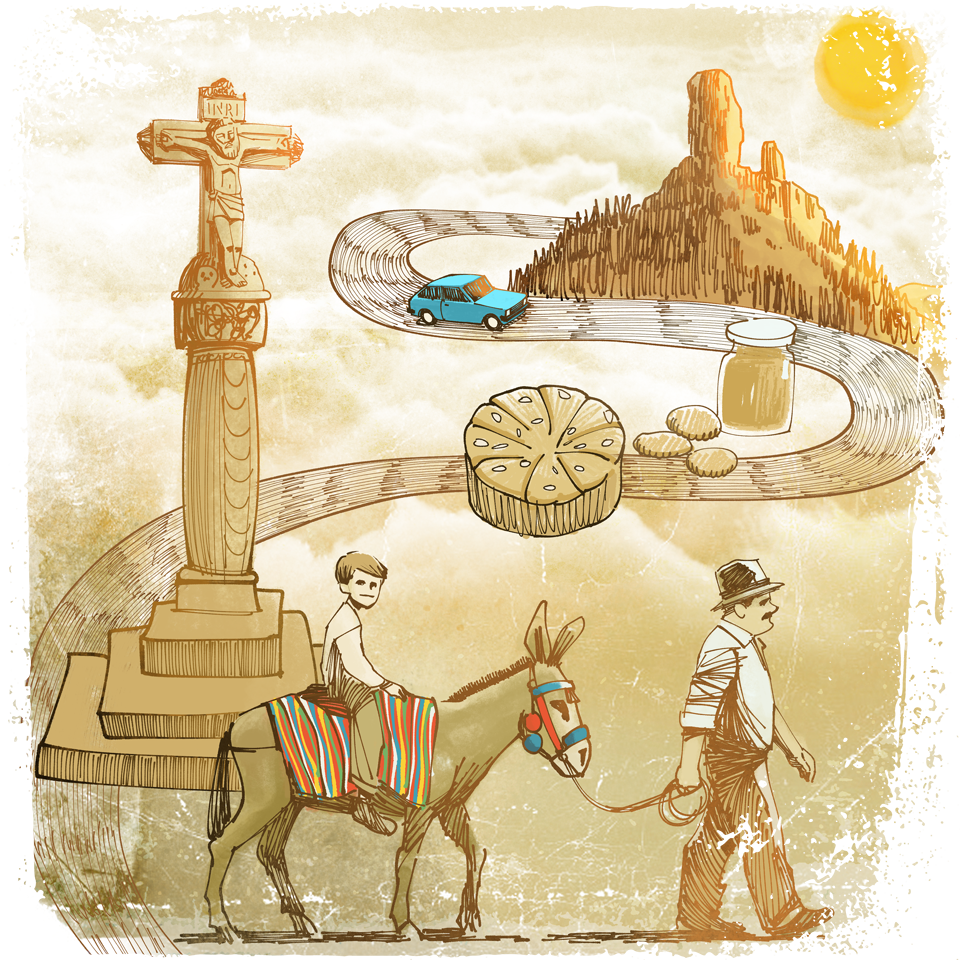

In my childhood Christmas presents were given only on Three Kings’ Day. Christmas was celebrated on the night of 24 December by going to church for the Midnight Mass and then kissing the foot of Jesus Child. I was eight years old when I managed to stay awake past midnight to walk the streets of the village where my grandmother used to live as if I were a big boy. My grandmother lived in Guía, just above where my grandfather had a grocery store with seven doors that sold everything you could imagine, although what most people came for was the Queso de Flor and the Christmas hampers around December time. I remember that my grandfather used to put up coloured lights above all the doors and that, just the day after I arrived from Guanarteme for the holidays, we would get into his car very early in the morning and drive along the endless roads to Tejeda.

Roque Nublo and Bentayga impressed me then as they still do now every time I climb the summit in search of happiness in the midst of ravines and cliffs where the energy of the earth seems to penetrate every pore of my soul. My grandfather would fill the car with marzipan and almond and honey bienmesabe cakes, but I was lucky enough to walk around the Nublo cake shop tasting all the sweets and looking at them as children look when they want to discover the magic of what they are observing, that process of making marzipan that was hard on the outside and soft on the inside, like many of the things I would encounter later along my way.

Before returning to Guía, we would always stop at the Cruz de Tejeda Parador, and I would climb on top of a little donkey called Sofía, next to whom I thought I looked like the cowboys in the Saturday afternoon films that were shown on the only TV channel there was at the time.

My grandmother used to prepare a nativity scene with coloured lights, pools of silver foil and figures that seemed real in her living room, especially when I woke up and that decoration made the dreams not disappear with the morning light. I felt the magic of the Three Kings when I placed them next to a cellophane and wooden castle, and when I saw that every day they were closer to the manger. I don’t remember more magical nights than those on the eve of Three Kings Day. I could hear them in the early hours of the morning. My overflowing illusion hardly let me sleep a wink and at five in the morning I was already setting off the ambulance sirens, the flashes of the remote-controlled cars or the bell of that first red bicycle with which I almost flew through the streets of the village.

I would find all those presents in front of the Nativity scene that my grandmother had created. My parents stayed those days in Guía, and as soon as I could, I would go to the Plaza Grande to enjoy all that din of toys, dolls, robots and children running after the regulation balls with those yellow cloth shirts of the Unión Deportiva Las Palmas.

Everything I am telling you happened before I was ten years old. One day, after school, my father took me to eat an ice cream at Peña de la Vieja and told me that my grandmother had died. We never went back to Guía. My grandfather closed the business and came to live with us in the house in Guanarteme. The first Christmas without my grandmother, everyone tried to make sure there was no sadness; but I didn’t go up to Tejeda with my grandfather, nor was the Nativity scene the same even though the Three Kings were on the same camels and left from the same castle in the East.

I already wrote the letter to the Three Kings myself and took it personally to the post box after my mother had corrected it. That year I didn’t ask for any material gift; I just wrote in the letter that I wanted to see my paternal grandmother again. I never met my maternal grandparents, although my mother told me so much about them that she managed to get them to sit at the Christmas Eve table like all those who have gone do every time someone remembers them. That Christmas Eve I couldn’t sleep a wink. I still believed I would see my grandmother, if only for a second, in the living room of that house where the sound of the waves of La Cícer could be heard.

I didn’t find my grandmother by my shoe when I got up at five in the morning. There was a surfboard, some books, some table games and a handwritten note in coloured ink. The Three Kings told me that my grandmother was on the beach, at the end of the horizon, but that to see her I had to learn to look for beauty beyond where my gaze ended. They told me not to despair, but never to stop looking for her. That’s what I did every day I was on the shore with my grandfather.

A neighbour, four years older than me, was one of the first surfers, and he was the one who taught me to ride waves when I wasn’t staring at the horizon. That’s what I still do every day, looking at the horizon and going down to the beach to let myself be carried away by the waves of La Cícer.

With my grandfather I learnt to build figures in the sand and to recreate volcanoes in which we would then put some papers that we would burn to see how the smoke mixed with the breeze. When Christmas came, we tried to create figures of the Three Kings, and little by little we succeeded; but then the tide would come in and wash away our long hours of work.

“..when I got to the area of La Puntilla,

I saw the sand-made Nativity..”

Today is Three Kings Day. I went down at five o’clock in the morning to walk along the beach, and when I got to the area of La Puntilla, I saw the sand-made Nativity. I asked the watchman to let me in for a moment, and I saw the imposing Three Kings created by Etual Ojeda while I listened in the background to the roar of the waves on the shore and also those breaking against La Barra, where the sound of the Atlantic is even more like the Atlantic about which the poets Alonso Quesada and Tomás Morales wrote.

I said goodbye to the watchman and went down to the shore for a swim while it was still dark on the beach. It was dawning little by little as I looked for my grandmother on the horizon where the lights of Tenerife were still visible. I see it every day since I learnt that Three Kings eve, that you can see whatever you want if you really look for it far beyond what we are told we can see or feel as humans.

Today is not a holiday in Düsseldorf. I was up most of the night developing a new virtual recreation programme for AI. To test what I was looking for I used some Super-8 films and a pile of photographs I had of my grandmother. Then I placed the laptop screen right in front of the window overlooking Las Canteras beach, in Punta Brava, next to what they call the Poet’s House.

There was my grandmother, on the horizon, among the waves that echoed behind the open glass. She looked at me and talked to me as if she were beside me. She always has been. This tale is really a letter to her. And all I have sought in my work with Artificial Intelligence is to be able to see her as a moment ago on a screen that disappeared before the almost infinite magnitude of the ocean. The Three Kings were right when they told me about it in that note they left forty-seven years ago in my house in Guanarteme.

About the author

Santiago Gil

The writer and journalist Santiago Gil (Guía, Gran Canaria, 1967) is the author of an extensive body of work that includes novels, short story collections, children’s books, poetry, memoirs, and a wide array of articles and columns in Canary Islands newspapers. His books often explore themes intrinsic to Canarian culture, blending contemporary topics with a touch of nostalgia and memories of rural life from days gone by. Santiago has been awarded the International Novel Prize Benito Pérez Galdós and the Esperanza Spínola Prize. His most recent works are the short story collection Rastros de vidas y palabras (Traces of Lives and Words) and the novel Los días de Guayedra (The Days of Guayedra).